Monday, December 26, 2011

Monday, November 28, 2011

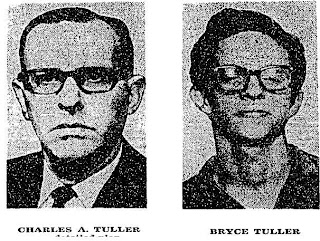

The Tullers: The communist cell in Alexandria and the Murders that Shocked Washington

On October 17, 1972, Charles Tuller turned in his resignation from his middle management job at the Department of Commerce. He would go on a leave of absence until the resignation became official on November 4. Tuller cited his diabetes and recent double hernia surgery as his reasons for stepping down. Colleagues had noted he looked like “death warmed over” so it didn’t come as a shock. Tuller was dedicated and worked hard at his job delivering government aid to minority businesses and many coworkers knew him as thoughtful and considerate. On the other hand, he had acquired odd views and had become obsessed with communist revolutionaries. Tuller’s coworkers and supervisors didn’t realize that the resignation was the catalyst that put in motion a carefully choreographed sequence of events.

On October 21, Charles’ son Bryce went on a three day pass from Ft. Bragg and would go AWOL when he didn’t return. Another son, Jonathan, called in sick from his lineman job at Vepco complaining of flu symptoms. William Graham, a family friend and former classmate of Bryce at TC Williams, went AWOL from his truck repair job at Ft. Benning. The four men gathered at Charles Tuller’s apartment at 3807 Executive Avenue in Alexandria, but they were short one man that backed out at the last minute when he realized they were serious about their plot to start a revolution in the United States. The Tullers had just moved into the apartment, which was in a building full of transient Washingtonians.

On October 24, Bryce and Charles went to American International Rent-a-car in Crystal City and procured a car. Charles signed as himself while Bryce signed his alias, J. Santino Wilson, a name also listed on their apartment’s lease (mysteriously, the clerk at the rental car place was adamant that Bryce’s picture did not look like the J. Santino Wilson who signed the rental agreement). Probably that evening, the plotters stole a C&P truck and uniforms from the lot at 115 S. Floyd St.

The next morning, William Graham and Charles Tuller drove their rental car towards Crystal City after leaving their brown 1967 Mercury Cougar at 20th and S. Fern St. The two Tuller sons, dressed in C&P uniforms, drove the stolen C&P truck and parked it on the corner of S. 20th and S. Clark St. next to a manhole that contained the telephone lines for the Crystal Plaza Complex. Amid the hustle of the morning rush, the two men would have been inconspicuous as they climbed into the hole and cut off the phones and alarms for entire area. However, as they worked the Assistant Residential Manager for the Crystal Plaza apartments peered down the hole out of curiosity. One of the men told him that water had “got into the splicing.”

Meanwhile, inside the Arlington Trust Company at 2001 Jefferson Davis Hwy something seemed strange when the phone lines suddenly went dead. One customer joked to the assistant manager “it’s a perfect time for a robbery.” Inside, Charles waited for his two sons and inquired at the Crystal World Travel Agency about the Alleghany Airlines schedule that day. At 10:30 AM on October 25, 1972, the Tuller sons, dressed as telephone repairmen entered the bank and told the manager they were there to repair the phone lines.

As they entered the bank, Charles followed and sat in the bank lobby unnoticed in the typical Washington dress of a shirt and tie sat. William Graham stood outside the back door near the getaway car. The two Tuller sons told the bank manager, Harry Candee, that they needed to get to the telephone box, so he escorted them to a back room. They entered the room, shut the door and told Candee it was a hold up. Candee resisted and they hit him with a blackjack. A teller, on her break in the back room, began to panic and may have screamed. As Candee continued resisting, one of the Tullers fired his gun, which mortally wounded Candee and grazed the bank teller.

At the same moment, the Cuban-born Arlington police officer Israel Gonzalez entered the bank and walked past Charles Tuller. Stories differ on why Officer Gonazalez entered the bank. He was either alerted by an employee unnerved by the dead phones or he was doing his routine check of the bank. Whatever the reason, he walked through the door as shots were fired in the back room. Gonzalez drew his gun and came into a glass hallway where he saw the Asst. Bank Manager open the door to the break room. Out of the room dashed the Tuller sons and Gonzalez fired two shots before the Tullers returned fire. When Charles Tuller saw this, he drew his gun and ordered the employees and customers on the ground. As Gonzalez and the Tuller sons exchanged fire, Charles Tuller shot him in the back causing Gonzalez to fall through glass doors leading to the back of the bank. As he lay dying from six gunshot wounds, Gonazlez managed to fire his gun and shoot Jonathan Tuller in the hand.

In a panic, the Tuller sons headed out the door towards 20th St. while Charles Tuller ran out the door leading to the apartment building. All three joined Graham on S. Clark St. and they piled into the getaway car. They left behind $160,000 in the bank vaults and a bloody scene of panicked customers and employees. With Jonathan bleeding from his wounded hand, the four men drove on S. 20th St., crossing Jefferson Davis Highway to S. Fern St. where they exchanged cars. Once they got into their other car, they headed south rushing away from the scene with their original plan in tatters. At some point they arrived in Winston-Salem where a friend of Bryce unwittingly gave them a new car. The generous girlfriend would arrive home to find her house surrounded by police hot on the trail of the bank robbers.

Charles Tuller remembered from his business travels that there was a surgeon in Houston he could trust. As the four men sped 1500 miles south west, they were in constant fear of the police. At one point, in Georgia, a state trooper passed them with his lights flashing and as he drove by, they held their loaded weapons ready to kill. Later, they stopped at a truck stop and one of the robbers, with a gun in his jacket, ran right into a police officer. There was tense moment before the officer said “excuse me.”

Five days after the robbery, the four men showed up at the Houston airport on October 30 and approached the gate of an Eastern Airlines plane boarding passengers headed for Atlanta and Syracuse. They waited until all the passengers had boarded the flight and Charles Tuller, leading the others, stormed the ramp of the plane. A ticket agent named Stanley Hubbard tried to stop Charles and they fell to the ground wrestling over his gun. Charles was able to pull the gun away and shoot Hubbard in the stomach. As Charles got up, Bryce Tuller shot Hubbard in the head. Hubbard lay dying, still holding Charles’ jacket as the four men rushed the plane. Outside, Wyatt Wilkinson refueled the plane when the engines suddenly started. Realizing the extreme danger of fuel and running jet engines, he ran into the terminal to get the plane to shut off where he found Hubbard and called an ambulance. He rushed down the ramp where he was met with gunfire and was hit three times, but survived the wounds.

The four hijackers stationed themselves throughout the plane and ordered the pilot to fly to Cuba. They told passengers to keep their hands on their heads for the entire 4 hour flight while Charles ranted over the intercom about his revolutionary leanings declaring “the revolution has started!” One African American passenger, Ron Pinckney, news director at WOL radio, had a gun pointed to his head and Charles asked him “What’s the matter black man? Are you afraid to die? Blacks who do not fight and give into the white man are slave niggers.” Charles then turned to another man and asked him what he did for a living. The man replied that he worked for IBM to which the Tuller replied “I didn’t like your looks when you got on! I should have killed you then!” The plan flew to New Orleans for refueling and went on to Cuba where the hijackers got off the plane and released the crew and passengers. The terrified hostages made it back to Miami the next afternoon. The four hijackers went into Cuban custody with no resistance.

Unfortunately, hijacking was a rather routine event in 1972, but Washingtonians would be shocked to learn that this band of radicals were locals living a typical Washington life, at least superficially. Since 1968, the US alone had 364 airliner hijackings with most of them being diverted to Cuba, but these hijackings had roots in a CIA tactic in which planes were hijacked from Cuba to the US to sow fear and confusion in the communist regime. After the CIA employed the tactic, leftists in the US began copying it as a way to gain entrance to the closest communist country. Cuban authorities considered these hijackers either CIA patsies or mentally ill, so they usually ended up in prison. The Tullers hijacking would accelerate FAA security changes already in the works leading to a comprehensive bill would pass Congress the next year. The changes brought universal screening procedures including bag inspection and scanning of passengers. As part of this comprehensive package, the CIA ended the use of hijacking as a covert action in Cuba and the US reached agreement with Cuba to prosecute or extradite hijackers. The Tuller group would be among the last hijackings on US soil and the deadliest, but a new wave would begin shortly, by radical Muslims borrowing tactics developed by leftist revolutionaries.

In addition to being among the last hijackings in the US, the Tuller band was the part of the rear guard of a fading movement. Communism was all but dead in the US and even among student radicals, communist philosophy held sway among only small militant groups. Nonetheless, the actions of the Tuller group would resuscitate quiescent fears of communist infiltration in government that were fading in Washington under a rising obsession with the deficit. By 1972, Washington was changing as conservative ideas began surpassing the New Deal, which was struggling to revive the economy. The old liberal constituencies were moving out of the mainstream of Washington as the once mighty coalition splintered. The splintered left brought out increasing frustration in the far left and this frustration bubbled into a series of violent events in the seventies. Tullers’ militant cell emerged out of nowhere in Alexandria, apparently disconnected from any other left-wing organization.

Tuller considered his group patriotic and the New York Times described him as “a handsome, aggressive, $26,000 per year bureaucrat who apparently believed the American dream could belong to everyone and worked to make it so.” However, beneath this hard working middle manager was anger at “the system” and its “oppression of blacks.” Racked with diabetes, Tuller became mentally unstable over the years and began turning to militancy as he became less satisfied with how the United States treated African-Americans. Tuller worked hard and could be charming, but could sputter with rage if “the system” held him up.

Tuller grew up comfortably in Toledo, OH, but when he was 9 his 4 year old brother was run over by a truck for which Tuller’s dad blamed him. Tuller later claimed, as his dad was on his death bed, he told Charles he would never forgive him for the death of his brother. This event shaped Charles’ life and would slowly erode his rationality. For years Charles would see a psychiatrist in New York as he dealt with his racking guilt. Despite this, Charles showed much promise in life as a man dedicated to helping others. Sometime in the early fifties, perhaps while attending college in New York City, he became involved in the civil rights movement. Living in Newark, NJ, he rose to a leadership position in the local chapter of the Congress on Racial Equity while working as a welfare case worker. Eventually he joined Attorney General Ramsey Clark’s Justice Department despite some concerns about his emerging leftist views (ironically Ramsey Clark would go on to become a Stalinist as the head of the International Action Center). Tuller would move through a few government jobs before landing in the Commerce Department where he specialized in helping minority businesses. He pursued the job with vigor, but he began to feel that his work was treating “symptoms and not the causes” of poverty and inequality.

By the late sixties he grew to hate white people and believed in standing with black and brown Americans over white Americans. A neighbor said “he was always ‘aginer’ and “against everything and everybody.” Around this time he embraced the philosophies of leftists like Mao Tse Tung and Che Guevara. Tuller probably found in Mao and Guevara a theory of empowerment for disenfranchised people and a way for them to organize to take over the power structures that oppressed them. Mao was leader of the Chinese revolution who developed a set of theories based on independence from the Soviet Union and distinctly Chinese solutions to problems. The revolution in China led to a new communist superpower that would not be subservient to the Soviet Union and would lead to global break-up of the communist movement. Mao introduced the “Three Worlds Theory”, which placed the US and Soviet Union in the first world, Europe and other developed countries as the second world, and the poorest unaligned nations as the third world. Mao believed the oppressed people of the third world would lead the Marxist revolution and, by extension, people of color were the revolutionary masses while white people were the people of privilege and counter-revolutionists.

Che Guevara admired Mao and believed he could extend his revolutionary theories to the peasants in South America. Admirers of Mao and Che in the US applied these ideas to say that white people in the US were the beneficiaries of “white privilege” and because of this they would tend to be counter-revolutionary. Thus, any good Maoist would align themselves with black and brown people because these people are the true proletariat. This simplistic view of American society led many Maoists to naïve views of poor and working class Americans which hampered their organizing. In other words, not many black folks want to overthrow capitalism and most white people are not fascists, which leads to a rapid breakdown of political theory for Maoists operating in the U.S.

Tuller didn’t embrace the American Maoists and sought an independent road. Perhaps viewing himself as a communist philosopher in his own right, Tuller never joined a communist organization because he felt they were too much in service to foreign governments. He took Mao’s nationalist independent views and applied them to the US where he hoped to recruit a revolutionary coalition of small farmers, small business owners and poor people to rise against the powers. True to the tactics of Mao and Che, he hoped, by organizing a small cadre, there would be a mobile and agile group of revolutionaries able to help local people take direct action. He considered his views to be “100% American”, patriotic and improving the lot of the people at the bottom of the heap.

Charles’ militancy and mental deterioration caused problems in his personal life. His wife, Edith, whom he married in 1949, put up with torrents of emotional abuse. If Charles needed someone to yell at, he would call Edith and tell her she was “a no good bitch”. Charles associated Edith with “the system” and had affairs with black women. He played out his frustration with whites by flaunting black girlfriends in front of coworkers and his wife challenging the sensibilities of the still very southern Washington area. When Tuller traveled to Houston on business he showed up at an office Christmas party with a black woman as his date causing uproar in this deep southern city. After the incident, his superiors had to ban him from travelling to Houston, which may have been part of his motivation for returning to the city and hijacking a plane. Tuller’s erratic behavior and infidelity forced his wife out of the house in March 1969 and their divorce became final in October 1971. Edith gave Charles custody of Bryce and Jonathan, who were attending high school at the time.

Charles remained close to his sons and was lenient with them. Their relationship, especially with Bryce, was more like friends than parental. The boys embraced their father’s leftist sympathies and joined the Students for Democratic Society chapters at Annandale High School and later TC Williams. When Bryce attended Annandale High School, he started an underground newspaper supporting leftist causes and caused a stir among students. The leftist activities of his sons caused Mr. Tuller to go to school often to defend them. He would use this time to rail against the system and threaten the principal. The Tuller house on Fontaine St. became a gathering point for a small group of radicals, which coalesced around the plot to rob a bank and start a revolution. By the late sixties, Charles Tuller’s ivy-league dress, cropped hair, and horn-rimmed glasses had evolved into long hair and a beard. At the time of the hijacking he sported a handle-bar moustache. When police searched his home they found marijuana plants growing in the back yard, parachutes stashed away, and piles of leftist propaganda.

As police learned in the days following the bank robbery, the hijackers had carefully planned the heist. Bryce Tuller sought training with the phone company as a cable splicer so he could learn which wires to cut and joined the army in February 1972 to learn to shoot a gun. Jonathan went to work at VEPCO to learn similar wiring skills. Charles Tuller robbed the First Virginia bank branch in Woodbridge of $5,822 in April in order to practice for the Crystal City holdup and to raise the funds needed for the bigger heist. Charles Tuller acquired at least one Lugar and went to Hunters’ Haven in Alexandria to buy a shotgun. The plotters regularly went camping to practice shooting their guns.

By the middle of 1972, the Tullers and their co-conspirators had settled on their plan. They were going to rob the bank in Crystal City and flee to the back woods of Canada where they could develop a leftist revolutionary commando unit. They hoped this unit could infiltrate the United States and organize a revolution. Charles Tuller believed this vanguard would incite a coalition of middle and working class Americans to rise up against capitalism.

When the plot went awry and two people lay dead, a bewildered city struggled to make sense how one of their own could go so crazy. They saw a man like many in this city who got up every morning and worked to help people with little or no thanks. Tuller was like many in the federal government, but he finally cracked. Shortly though, the media narration reverted to days of the red scare as an old familiar paranoia set into the city.

The Tullers actions brought back old red scare hysteria and briefly whipped the Washington establishment up as their old anxiety about communist infiltration of government came back to life. The columnist Victor Riesel reported that Tuller had been busted engaging in gay activities in New York and accused him of being involved in the incredibly square sounding “white bohemia”. This was a common accusation hurled at leftist activists as support for gay rights conflated with being gay. As Joe McCarthy succinctly put it, only “communists and cocksuckers” were against the anti-communist witch-hunt.

However, it would have been surprising if Tuller was gay given his devotion to the totalitarian wing of the left and his well-know dalliances with many women. The communist regimes that Tuller admired were strongly anti-gay, often considering it a mental illness or the result of capitalist excess. Neither Cuba nor China tolerated gays at this time and have been behind the US in recognizing the civil rights of gays. Perhaps Tuller encountered fellow leftist who were gay, but it would be strange for him to be devoted to Mao and supportive of gays.

As some columnists tried to stoke hysteria, others struggled to piece together an explanation for Charles Tuller and his followers. Newspapers published profiles of Tuller, but they couldn’t arrive at a rational reason for Tuller’s madness. Some tried to portray him as deviant, some blamed childhood trauma, and some placed him in the context of a wider civil rights movement, but none could make sense of the three dead men.

As the media worked to put together a narrative, government officials faced a nightmare scenario. Reporters wrote about Tuller’s work ethic and passion, but simultaneously wondered how a guy with such radical views could get a job with the government. Through conversations with all the people in Tuller’s life, it was clear that he was good at his job and could be a very charming guy, but people were also troubled by his views and temper. This put government officials in a difficult spot because if they fired him for his communist views, they risked seeing a headline about reds infiltrating government and if they accused him of mental illness, they had a high legal hurdle to leap. Given that he was doing well at his job, his supervisors did nothing, which proved to be a bad decision.

Newspapers began calling for the establishment of an Employee Security Board to root out radicals in government despite it being clear that the government was not overrun with reds. Roger Wilkins, who had recently gone to work for the editorial page of the Washington Post, hired Tuller in the Commerce Department, but he told reporters that Tuller “struck people in a mean way” and he told his successor at Commerce to watch Tuller. However, no one took any action against him during his time.

As Washington debated what the robbery and murders meant, the Tullers and Graham landed in Cuba and were immediately taken into custody. They were held in solitary confinement for months and given little food and no new clothes. Once released the Tullers were sent to labor in sugar cane fields, which they would later describe as “a living hell”. The Tullers wanted to leave after the first day, but Cuban authorities would not allow them to go. They barely subsisted for months in a rundown hotel with no running water and ate mostly rice. Later, Bryce Tuller claimed they were “starving to death” during this time. At night, in a nearby courtyard, they could hear the firing squads execute anti-Castro Cubans.

On the other hand, Graham was studying languages and history at the University of Havana by 1973. In his off time, Graham enjoyed swimming and volunteered for construction crews building apartment houses. He condemned the Tullers as the murderers of the three victims in the US and declared that he had broken with them. Charles Tuller was angry with Graham because he blamed his sloppiness for the murders in the US and Graham decided that Charles Tuller was mentally unbalanced. By 1975, Graham has left the University and had become a night foreman at a print shop, which his mother would only describe as “involuntary.”

Charles Tuller’s health turned for the worse in Cuba and he may have been hospitalized after a heart attack. On June 20, 1975, Cuban authorities gave Charles and his two sons $1,400 and some false identification papers. They put them on a series of flights leading to Miami. Amazingly the trio walked through the airport undetected and entered the United States. As they made their way back to Alexandria, they attempted to rob and Kmart in Fayetteville, NC. Bryce Tuller entered the manager’s office and showed his sawed-off shotgun under his coat. He took the cash and demanded the safe be opened. As the safe was opened a security guard distracted him and an enterprising manager grabbed a stool leg and began beating Bryce. The police arrived to find Bryce held at gunpoint with his own shotgun.

Charles and Jonathan fled the Kmart reaching Alexandria where they checked into a hotel and laid in bed with their shotguns. When they learned that Bryce was in jail, they decided it was time to turn themselves in. They went to the Washington FBI field office in the Old Post Office building and told the security guard that they wanted to see an FBI agent. They were sent to the fifth floor where they found an agent and told him calmly they were wanted for bank robbery and murder. The head of the DC field office recalled, “I had just come back from lunch and someone told me Charles Tuller and his son have just surrendered.” He went on to say “I’ve never been so surprised at anything in my life.”

As the Tullers stood before the judge, they wore the same clothes they had on the fateful day three years earlier. After a short trial the judge sentenced each of them to 100 years in prison. Shortly after his conviction, reporters interviewed Charles Tuller who said he had “no regrets” about shooting Officer Gonzalez in the back. When bank manager Harry Candee came up, he snickered calling his death “unfortunate” and saying “I guess he was doing his job the way he saw it”. In the end, Tuller considered his actions honorable and done for the greater cause of his country.

The sage of the Tullers didn’t end with their convictions. In 1984, Bryce Tuller seized an opportunity and escaped the Bland Correctional Center near Roanoke by walking past a guard and through an unlocked door. He remained on the lam for 2 days before police caught him walking along Interstate 77 near the West Virginia border exhausted from his time in the woods. In the late seventies, William Graham slipped back into the US and federal authorities got wind of it, but they couldn’t find him. Graham moved to San Francisco and had a successful career until he saw his case on America’s Most Wanted in 1993 and decided it was time to end his run from the law.

Today Graham, Bryce Tuller, and Jonathan Tuller are serving life sentences while Charles Tuller died in prison in 1988.

On October 21, Charles’ son Bryce went on a three day pass from Ft. Bragg and would go AWOL when he didn’t return. Another son, Jonathan, called in sick from his lineman job at Vepco complaining of flu symptoms. William Graham, a family friend and former classmate of Bryce at TC Williams, went AWOL from his truck repair job at Ft. Benning. The four men gathered at Charles Tuller’s apartment at 3807 Executive Avenue in Alexandria, but they were short one man that backed out at the last minute when he realized they were serious about their plot to start a revolution in the United States. The Tullers had just moved into the apartment, which was in a building full of transient Washingtonians.

On October 24, Bryce and Charles went to American International Rent-a-car in Crystal City and procured a car. Charles signed as himself while Bryce signed his alias, J. Santino Wilson, a name also listed on their apartment’s lease (mysteriously, the clerk at the rental car place was adamant that Bryce’s picture did not look like the J. Santino Wilson who signed the rental agreement). Probably that evening, the plotters stole a C&P truck and uniforms from the lot at 115 S. Floyd St.

The next morning, William Graham and Charles Tuller drove their rental car towards Crystal City after leaving their brown 1967 Mercury Cougar at 20th and S. Fern St. The two Tuller sons, dressed in C&P uniforms, drove the stolen C&P truck and parked it on the corner of S. 20th and S. Clark St. next to a manhole that contained the telephone lines for the Crystal Plaza Complex. Amid the hustle of the morning rush, the two men would have been inconspicuous as they climbed into the hole and cut off the phones and alarms for entire area. However, as they worked the Assistant Residential Manager for the Crystal Plaza apartments peered down the hole out of curiosity. One of the men told him that water had “got into the splicing.”

Meanwhile, inside the Arlington Trust Company at 2001 Jefferson Davis Hwy something seemed strange when the phone lines suddenly went dead. One customer joked to the assistant manager “it’s a perfect time for a robbery.” Inside, Charles waited for his two sons and inquired at the Crystal World Travel Agency about the Alleghany Airlines schedule that day. At 10:30 AM on October 25, 1972, the Tuller sons, dressed as telephone repairmen entered the bank and told the manager they were there to repair the phone lines.

As they entered the bank, Charles followed and sat in the bank lobby unnoticed in the typical Washington dress of a shirt and tie sat. William Graham stood outside the back door near the getaway car. The two Tuller sons told the bank manager, Harry Candee, that they needed to get to the telephone box, so he escorted them to a back room. They entered the room, shut the door and told Candee it was a hold up. Candee resisted and they hit him with a blackjack. A teller, on her break in the back room, began to panic and may have screamed. As Candee continued resisting, one of the Tullers fired his gun, which mortally wounded Candee and grazed the bank teller.

At the same moment, the Cuban-born Arlington police officer Israel Gonzalez entered the bank and walked past Charles Tuller. Stories differ on why Officer Gonazalez entered the bank. He was either alerted by an employee unnerved by the dead phones or he was doing his routine check of the bank. Whatever the reason, he walked through the door as shots were fired in the back room. Gonzalez drew his gun and came into a glass hallway where he saw the Asst. Bank Manager open the door to the break room. Out of the room dashed the Tuller sons and Gonzalez fired two shots before the Tullers returned fire. When Charles Tuller saw this, he drew his gun and ordered the employees and customers on the ground. As Gonzalez and the Tuller sons exchanged fire, Charles Tuller shot him in the back causing Gonzalez to fall through glass doors leading to the back of the bank. As he lay dying from six gunshot wounds, Gonazlez managed to fire his gun and shoot Jonathan Tuller in the hand.

In a panic, the Tuller sons headed out the door towards 20th St. while Charles Tuller ran out the door leading to the apartment building. All three joined Graham on S. Clark St. and they piled into the getaway car. They left behind $160,000 in the bank vaults and a bloody scene of panicked customers and employees. With Jonathan bleeding from his wounded hand, the four men drove on S. 20th St., crossing Jefferson Davis Highway to S. Fern St. where they exchanged cars. Once they got into their other car, they headed south rushing away from the scene with their original plan in tatters. At some point they arrived in Winston-Salem where a friend of Bryce unwittingly gave them a new car. The generous girlfriend would arrive home to find her house surrounded by police hot on the trail of the bank robbers.

Charles Tuller remembered from his business travels that there was a surgeon in Houston he could trust. As the four men sped 1500 miles south west, they were in constant fear of the police. At one point, in Georgia, a state trooper passed them with his lights flashing and as he drove by, they held their loaded weapons ready to kill. Later, they stopped at a truck stop and one of the robbers, with a gun in his jacket, ran right into a police officer. There was tense moment before the officer said “excuse me.”

Five days after the robbery, the four men showed up at the Houston airport on October 30 and approached the gate of an Eastern Airlines plane boarding passengers headed for Atlanta and Syracuse. They waited until all the passengers had boarded the flight and Charles Tuller, leading the others, stormed the ramp of the plane. A ticket agent named Stanley Hubbard tried to stop Charles and they fell to the ground wrestling over his gun. Charles was able to pull the gun away and shoot Hubbard in the stomach. As Charles got up, Bryce Tuller shot Hubbard in the head. Hubbard lay dying, still holding Charles’ jacket as the four men rushed the plane. Outside, Wyatt Wilkinson refueled the plane when the engines suddenly started. Realizing the extreme danger of fuel and running jet engines, he ran into the terminal to get the plane to shut off where he found Hubbard and called an ambulance. He rushed down the ramp where he was met with gunfire and was hit three times, but survived the wounds.

The four hijackers stationed themselves throughout the plane and ordered the pilot to fly to Cuba. They told passengers to keep their hands on their heads for the entire 4 hour flight while Charles ranted over the intercom about his revolutionary leanings declaring “the revolution has started!” One African American passenger, Ron Pinckney, news director at WOL radio, had a gun pointed to his head and Charles asked him “What’s the matter black man? Are you afraid to die? Blacks who do not fight and give into the white man are slave niggers.” Charles then turned to another man and asked him what he did for a living. The man replied that he worked for IBM to which the Tuller replied “I didn’t like your looks when you got on! I should have killed you then!” The plan flew to New Orleans for refueling and went on to Cuba where the hijackers got off the plane and released the crew and passengers. The terrified hostages made it back to Miami the next afternoon. The four hijackers went into Cuban custody with no resistance.

Unfortunately, hijacking was a rather routine event in 1972, but Washingtonians would be shocked to learn that this band of radicals were locals living a typical Washington life, at least superficially. Since 1968, the US alone had 364 airliner hijackings with most of them being diverted to Cuba, but these hijackings had roots in a CIA tactic in which planes were hijacked from Cuba to the US to sow fear and confusion in the communist regime. After the CIA employed the tactic, leftists in the US began copying it as a way to gain entrance to the closest communist country. Cuban authorities considered these hijackers either CIA patsies or mentally ill, so they usually ended up in prison. The Tullers hijacking would accelerate FAA security changes already in the works leading to a comprehensive bill would pass Congress the next year. The changes brought universal screening procedures including bag inspection and scanning of passengers. As part of this comprehensive package, the CIA ended the use of hijacking as a covert action in Cuba and the US reached agreement with Cuba to prosecute or extradite hijackers. The Tuller group would be among the last hijackings on US soil and the deadliest, but a new wave would begin shortly, by radical Muslims borrowing tactics developed by leftist revolutionaries.

In addition to being among the last hijackings in the US, the Tuller band was the part of the rear guard of a fading movement. Communism was all but dead in the US and even among student radicals, communist philosophy held sway among only small militant groups. Nonetheless, the actions of the Tuller group would resuscitate quiescent fears of communist infiltration in government that were fading in Washington under a rising obsession with the deficit. By 1972, Washington was changing as conservative ideas began surpassing the New Deal, which was struggling to revive the economy. The old liberal constituencies were moving out of the mainstream of Washington as the once mighty coalition splintered. The splintered left brought out increasing frustration in the far left and this frustration bubbled into a series of violent events in the seventies. Tullers’ militant cell emerged out of nowhere in Alexandria, apparently disconnected from any other left-wing organization.

Tuller considered his group patriotic and the New York Times described him as “a handsome, aggressive, $26,000 per year bureaucrat who apparently believed the American dream could belong to everyone and worked to make it so.” However, beneath this hard working middle manager was anger at “the system” and its “oppression of blacks.” Racked with diabetes, Tuller became mentally unstable over the years and began turning to militancy as he became less satisfied with how the United States treated African-Americans. Tuller worked hard and could be charming, but could sputter with rage if “the system” held him up.

Tuller grew up comfortably in Toledo, OH, but when he was 9 his 4 year old brother was run over by a truck for which Tuller’s dad blamed him. Tuller later claimed, as his dad was on his death bed, he told Charles he would never forgive him for the death of his brother. This event shaped Charles’ life and would slowly erode his rationality. For years Charles would see a psychiatrist in New York as he dealt with his racking guilt. Despite this, Charles showed much promise in life as a man dedicated to helping others. Sometime in the early fifties, perhaps while attending college in New York City, he became involved in the civil rights movement. Living in Newark, NJ, he rose to a leadership position in the local chapter of the Congress on Racial Equity while working as a welfare case worker. Eventually he joined Attorney General Ramsey Clark’s Justice Department despite some concerns about his emerging leftist views (ironically Ramsey Clark would go on to become a Stalinist as the head of the International Action Center). Tuller would move through a few government jobs before landing in the Commerce Department where he specialized in helping minority businesses. He pursued the job with vigor, but he began to feel that his work was treating “symptoms and not the causes” of poverty and inequality.

By the late sixties he grew to hate white people and believed in standing with black and brown Americans over white Americans. A neighbor said “he was always ‘aginer’ and “against everything and everybody.” Around this time he embraced the philosophies of leftists like Mao Tse Tung and Che Guevara. Tuller probably found in Mao and Guevara a theory of empowerment for disenfranchised people and a way for them to organize to take over the power structures that oppressed them. Mao was leader of the Chinese revolution who developed a set of theories based on independence from the Soviet Union and distinctly Chinese solutions to problems. The revolution in China led to a new communist superpower that would not be subservient to the Soviet Union and would lead to global break-up of the communist movement. Mao introduced the “Three Worlds Theory”, which placed the US and Soviet Union in the first world, Europe and other developed countries as the second world, and the poorest unaligned nations as the third world. Mao believed the oppressed people of the third world would lead the Marxist revolution and, by extension, people of color were the revolutionary masses while white people were the people of privilege and counter-revolutionists.

Che Guevara admired Mao and believed he could extend his revolutionary theories to the peasants in South America. Admirers of Mao and Che in the US applied these ideas to say that white people in the US were the beneficiaries of “white privilege” and because of this they would tend to be counter-revolutionary. Thus, any good Maoist would align themselves with black and brown people because these people are the true proletariat. This simplistic view of American society led many Maoists to naïve views of poor and working class Americans which hampered their organizing. In other words, not many black folks want to overthrow capitalism and most white people are not fascists, which leads to a rapid breakdown of political theory for Maoists operating in the U.S.

Tuller didn’t embrace the American Maoists and sought an independent road. Perhaps viewing himself as a communist philosopher in his own right, Tuller never joined a communist organization because he felt they were too much in service to foreign governments. He took Mao’s nationalist independent views and applied them to the US where he hoped to recruit a revolutionary coalition of small farmers, small business owners and poor people to rise against the powers. True to the tactics of Mao and Che, he hoped, by organizing a small cadre, there would be a mobile and agile group of revolutionaries able to help local people take direct action. He considered his views to be “100% American”, patriotic and improving the lot of the people at the bottom of the heap.

Charles’ militancy and mental deterioration caused problems in his personal life. His wife, Edith, whom he married in 1949, put up with torrents of emotional abuse. If Charles needed someone to yell at, he would call Edith and tell her she was “a no good bitch”. Charles associated Edith with “the system” and had affairs with black women. He played out his frustration with whites by flaunting black girlfriends in front of coworkers and his wife challenging the sensibilities of the still very southern Washington area. When Tuller traveled to Houston on business he showed up at an office Christmas party with a black woman as his date causing uproar in this deep southern city. After the incident, his superiors had to ban him from travelling to Houston, which may have been part of his motivation for returning to the city and hijacking a plane. Tuller’s erratic behavior and infidelity forced his wife out of the house in March 1969 and their divorce became final in October 1971. Edith gave Charles custody of Bryce and Jonathan, who were attending high school at the time.

Charles remained close to his sons and was lenient with them. Their relationship, especially with Bryce, was more like friends than parental. The boys embraced their father’s leftist sympathies and joined the Students for Democratic Society chapters at Annandale High School and later TC Williams. When Bryce attended Annandale High School, he started an underground newspaper supporting leftist causes and caused a stir among students. The leftist activities of his sons caused Mr. Tuller to go to school often to defend them. He would use this time to rail against the system and threaten the principal. The Tuller house on Fontaine St. became a gathering point for a small group of radicals, which coalesced around the plot to rob a bank and start a revolution. By the late sixties, Charles Tuller’s ivy-league dress, cropped hair, and horn-rimmed glasses had evolved into long hair and a beard. At the time of the hijacking he sported a handle-bar moustache. When police searched his home they found marijuana plants growing in the back yard, parachutes stashed away, and piles of leftist propaganda.

As police learned in the days following the bank robbery, the hijackers had carefully planned the heist. Bryce Tuller sought training with the phone company as a cable splicer so he could learn which wires to cut and joined the army in February 1972 to learn to shoot a gun. Jonathan went to work at VEPCO to learn similar wiring skills. Charles Tuller robbed the First Virginia bank branch in Woodbridge of $5,822 in April in order to practice for the Crystal City holdup and to raise the funds needed for the bigger heist. Charles Tuller acquired at least one Lugar and went to Hunters’ Haven in Alexandria to buy a shotgun. The plotters regularly went camping to practice shooting their guns.

By the middle of 1972, the Tullers and their co-conspirators had settled on their plan. They were going to rob the bank in Crystal City and flee to the back woods of Canada where they could develop a leftist revolutionary commando unit. They hoped this unit could infiltrate the United States and organize a revolution. Charles Tuller believed this vanguard would incite a coalition of middle and working class Americans to rise up against capitalism.

When the plot went awry and two people lay dead, a bewildered city struggled to make sense how one of their own could go so crazy. They saw a man like many in this city who got up every morning and worked to help people with little or no thanks. Tuller was like many in the federal government, but he finally cracked. Shortly though, the media narration reverted to days of the red scare as an old familiar paranoia set into the city.

The Tullers actions brought back old red scare hysteria and briefly whipped the Washington establishment up as their old anxiety about communist infiltration of government came back to life. The columnist Victor Riesel reported that Tuller had been busted engaging in gay activities in New York and accused him of being involved in the incredibly square sounding “white bohemia”. This was a common accusation hurled at leftist activists as support for gay rights conflated with being gay. As Joe McCarthy succinctly put it, only “communists and cocksuckers” were against the anti-communist witch-hunt.

However, it would have been surprising if Tuller was gay given his devotion to the totalitarian wing of the left and his well-know dalliances with many women. The communist regimes that Tuller admired were strongly anti-gay, often considering it a mental illness or the result of capitalist excess. Neither Cuba nor China tolerated gays at this time and have been behind the US in recognizing the civil rights of gays. Perhaps Tuller encountered fellow leftist who were gay, but it would be strange for him to be devoted to Mao and supportive of gays.

As some columnists tried to stoke hysteria, others struggled to piece together an explanation for Charles Tuller and his followers. Newspapers published profiles of Tuller, but they couldn’t arrive at a rational reason for Tuller’s madness. Some tried to portray him as deviant, some blamed childhood trauma, and some placed him in the context of a wider civil rights movement, but none could make sense of the three dead men.

As the media worked to put together a narrative, government officials faced a nightmare scenario. Reporters wrote about Tuller’s work ethic and passion, but simultaneously wondered how a guy with such radical views could get a job with the government. Through conversations with all the people in Tuller’s life, it was clear that he was good at his job and could be a very charming guy, but people were also troubled by his views and temper. This put government officials in a difficult spot because if they fired him for his communist views, they risked seeing a headline about reds infiltrating government and if they accused him of mental illness, they had a high legal hurdle to leap. Given that he was doing well at his job, his supervisors did nothing, which proved to be a bad decision.

Newspapers began calling for the establishment of an Employee Security Board to root out radicals in government despite it being clear that the government was not overrun with reds. Roger Wilkins, who had recently gone to work for the editorial page of the Washington Post, hired Tuller in the Commerce Department, but he told reporters that Tuller “struck people in a mean way” and he told his successor at Commerce to watch Tuller. However, no one took any action against him during his time.

As Washington debated what the robbery and murders meant, the Tullers and Graham landed in Cuba and were immediately taken into custody. They were held in solitary confinement for months and given little food and no new clothes. Once released the Tullers were sent to labor in sugar cane fields, which they would later describe as “a living hell”. The Tullers wanted to leave after the first day, but Cuban authorities would not allow them to go. They barely subsisted for months in a rundown hotel with no running water and ate mostly rice. Later, Bryce Tuller claimed they were “starving to death” during this time. At night, in a nearby courtyard, they could hear the firing squads execute anti-Castro Cubans.

On the other hand, Graham was studying languages and history at the University of Havana by 1973. In his off time, Graham enjoyed swimming and volunteered for construction crews building apartment houses. He condemned the Tullers as the murderers of the three victims in the US and declared that he had broken with them. Charles Tuller was angry with Graham because he blamed his sloppiness for the murders in the US and Graham decided that Charles Tuller was mentally unbalanced. By 1975, Graham has left the University and had become a night foreman at a print shop, which his mother would only describe as “involuntary.”

Charles Tuller’s health turned for the worse in Cuba and he may have been hospitalized after a heart attack. On June 20, 1975, Cuban authorities gave Charles and his two sons $1,400 and some false identification papers. They put them on a series of flights leading to Miami. Amazingly the trio walked through the airport undetected and entered the United States. As they made their way back to Alexandria, they attempted to rob and Kmart in Fayetteville, NC. Bryce Tuller entered the manager’s office and showed his sawed-off shotgun under his coat. He took the cash and demanded the safe be opened. As the safe was opened a security guard distracted him and an enterprising manager grabbed a stool leg and began beating Bryce. The police arrived to find Bryce held at gunpoint with his own shotgun.

Charles and Jonathan fled the Kmart reaching Alexandria where they checked into a hotel and laid in bed with their shotguns. When they learned that Bryce was in jail, they decided it was time to turn themselves in. They went to the Washington FBI field office in the Old Post Office building and told the security guard that they wanted to see an FBI agent. They were sent to the fifth floor where they found an agent and told him calmly they were wanted for bank robbery and murder. The head of the DC field office recalled, “I had just come back from lunch and someone told me Charles Tuller and his son have just surrendered.” He went on to say “I’ve never been so surprised at anything in my life.”

As the Tullers stood before the judge, they wore the same clothes they had on the fateful day three years earlier. After a short trial the judge sentenced each of them to 100 years in prison. Shortly after his conviction, reporters interviewed Charles Tuller who said he had “no regrets” about shooting Officer Gonzalez in the back. When bank manager Harry Candee came up, he snickered calling his death “unfortunate” and saying “I guess he was doing his job the way he saw it”. In the end, Tuller considered his actions honorable and done for the greater cause of his country.

The sage of the Tullers didn’t end with their convictions. In 1984, Bryce Tuller seized an opportunity and escaped the Bland Correctional Center near Roanoke by walking past a guard and through an unlocked door. He remained on the lam for 2 days before police caught him walking along Interstate 77 near the West Virginia border exhausted from his time in the woods. In the late seventies, William Graham slipped back into the US and federal authorities got wind of it, but they couldn’t find him. Graham moved to San Francisco and had a successful career until he saw his case on America’s Most Wanted in 1993 and decided it was time to end his run from the law.

Today Graham, Bryce Tuller, and Jonathan Tuller are serving life sentences while Charles Tuller died in prison in 1988.

Saturday, November 5, 2011

Blitzkrieg Bop in Bailey's Crossroads: Louie's Rock City and the Birth of Punk in DC

In June 1975, Hawaiian restaurateur Johnny Kao rented the former site of Giant Food at at 3501 S. Jefferson St. in Bailey’s Crossroads and turned it into a Las Vegas styled lounge called the Royal Hawaiian Supper Club. The club opened to much anticipation and fanfare in December 1975 with Patti Page and a comedian named Freddie Roman headlining the first week. The club was beautiful by all accounts and appealed to the over-thirty suburbanites driven from the city by crime and racial tension. In short order the club featured The Platters, Phyllis Diller, Eddie Fisher, The Smothers Brothers, Billy Eckstine, The Supremes (post Diana Ross), and Bobby Rydell. However, the article on the club’s opening night sounded some ominous warnings such as the strange location of this glitzy club in the middle of a suburban shopping mall and, worst of all, on opening night it was only three-fourths full. Patti Page expressed surprise at the club’s location and Roman joked about performing in a shopping center.

By June of 1976, the club ran into financial problems and was sold to new owner named Mike Munley. Mike Munley had been co-owner of the Bayou in the fifties with the Vincent and Tony Tramonte (in 1980 after selling the Bayou, Vincent Tramonte would start the Italian Store on Lee Highway). After he was bought out from the Bayou, Munley ran the Place Where Louie Dwells located originally at 1000 4th Street, SW in DC and later moved to 1011 Wesley Place, SW. It was a typical lounge in the Southwest waterfront area opening around 1966 featuring mediocre food and lounge jazz. Louie’s gained some brief notoriety when the local piano-man Samuel Marks collapsed at the piano and died. When Munley bought the Royal Hawaiian, he began to work to change the name of his new restaurant to the Place Where Louie Dwells.

While Munley worked on the name change, he expanded the line up with his first act being the country singer Lynn Anderson of “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden” fame. In July 1976, one of the last acts to appear at the Royal Hawaiian Supper Club was the Mills Brothers during the week they would entertain the ever-square Gerald Ford at the White House. Munley also inherited a dire financial situation and checks sent to entertainers bounced, which led to a $15,000 lawsuit by singer Jack Albertson. The club featured artists such as the Amazing Kreskin, Brenda Lee, and Sarah Vaughn.

Probably driven by economics more than anything, in October, 1977, the name of the club had become Louie’s Rock Concert City, but it was commonly known as Louie’s Rock City and they began to bring in rock music in the hopes of saving the business. In November 1977 Summersault and Cactus played, a few weeks later were Dr. Feelgood and Gentle Giant, Rick Derringer, Johnny Winter. Immediately, it became the place in NOVA for the burgeoning hard rock scene hosting brand new acts like Judas Priest before they hit the big time. Even though the club focused on rock music, it was cool to the new punk music coming out of New York. In 1977, the club cancelled the legendary punk bank the Nerves when they got a look at the band members.

By 1979, the owners of Louie’s Rock City accepted punk enough to host the Ramones. At first the Ramones were supposed to play on April 2, but it appears that show was cancelled for reasons lost to history. The Ramones would play Louie’s on July 27 and the show would be a cultural marker for the DC area. Of course, this wasn’t the Ramones first appearance in the DC area. They had played the Childe Harold October 22-24, 1976; October 11, 1977 at the Bayou; October 15, 1977 opening for Iggy Pop at the Baltimore Civic Center; and the Cellar Door with the Runaways March 19, 1978.

This time it was different because the punk scene in DC was coalescing around some kids for Northwest Washington, suburban Maryland and Northern Virginia. A young music promoter named Seth Hurwitz saw the Ramones were coming to Louie’s and decided to bring them down a day early for the premiere of the Ramones’ new movie “Rock and Roll High School” at the Ontario Theatre in Adams Morgan. On July 25, 1979, The Slickee Boys and Razz played to a packed crowd as the Ramones signed autographs and mingled. For many kids, this was the beginning of punk in Washington and Hurwitz would go on to own the 9:30 Club and founded the musical promotion company Live Nation. As “Rock and Roll High School” rolled fans danced in aisles to the music and cheered through best scenes. The newspaper described the crowd as a mix of punks, hippies, and lawyers ranging from “preteens to aging rockers”. The next day, the Ramones signed records at Penguin Feather at 5850 Leesburg Pike. The building has been torn down, but it was located roughly on the parking lot of the recently shuttered Borders Books in Crossroads Center.

Sensing the excitement in the city, the Washington Post was on hand for the Ramones gig at Louie’s on July 27, 1979. Initially the Post dislike punk because it upset the neat order of Washington, which was neatly divided into the three strata of the city, black people, polite Washington, and hippies. Punk didn’t fit and the old curmudgeon of DC music Richard Harrington declared punk was the “music for empty spaces of the mind.” In his review of the earlier Ramones show at the Bayou, he sounded a hopeful tone that punk was a passing fad when he said that half the crowd was there “out of curiosity” and “a number left after it became apparent that a Ramones set consists of monochord songs.” It’s a bitch being a cultural arbiter when the great unwashed don’t heed your cultural orders.

In a rare moment of wisdom, the WaPo hired a decent reporter, named Joe Sasfy, to cover the new music scene. Sasfy managed to straddle his reporting between a sympathetic eye towards the new sounds, but always writing in a way that polite Washington could understand. Wisely, Harrington was allowed to go to bed at a decent hour on the night the Ramones played Louie’s and the Post sent Sasfy to capture a cultural moment for the DC area. Sasfy noted in his article the Ramones fans showed up and were surprised by Louie’s dress policy and had to sew the tears in their clothes to get in. As the soon-to-be singer for Minor Threat and later Fugazi, Ian MacKaye recalled:

It’s surprising that Louie’s had a dress policy given they hosted Judas Priest and other hard rock bands. This incident may have stemmed from the club owners nervousness about hosting a punk show and was implemented as a way to control the crowd. Despite this barrier, the crowd packed into Louie’s to see one of the great Ramones shows. One recent high school graduate named Henry Garfield was there. The show would transform his life and he would form a band called Black Flag and change his name to Henry Rollins. Rollins speaks often about his experience at the show saying he “never got over that gig”. Later he said,

These few days the Ramones spent in the DC area would change the landscape of the city and in short order it would become one of the centers of punk music in the United States. The Ramones at Louie’s would echo through the years as DC developed a unique and thriving punk and new music scene that would bring sounds and clubs the city now considers routine.

As for Louie’s Rock City, the club would go on to host memorable shows by Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry in 1981. By this mid-eighties, it became primarily known for heavy metal and hosted a regular Battle of the Bands featuring local heavy metal bands trying to break into stardom. The club closed in 1989 and became a Chinese restaurant. Today it is the Babylon Futbol Club featuring soccer, Arabic, Caribbean, and Latin music.

By June of 1976, the club ran into financial problems and was sold to new owner named Mike Munley. Mike Munley had been co-owner of the Bayou in the fifties with the Vincent and Tony Tramonte (in 1980 after selling the Bayou, Vincent Tramonte would start the Italian Store on Lee Highway). After he was bought out from the Bayou, Munley ran the Place Where Louie Dwells located originally at 1000 4th Street, SW in DC and later moved to 1011 Wesley Place, SW. It was a typical lounge in the Southwest waterfront area opening around 1966 featuring mediocre food and lounge jazz. Louie’s gained some brief notoriety when the local piano-man Samuel Marks collapsed at the piano and died. When Munley bought the Royal Hawaiian, he began to work to change the name of his new restaurant to the Place Where Louie Dwells.

While Munley worked on the name change, he expanded the line up with his first act being the country singer Lynn Anderson of “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden” fame. In July 1976, one of the last acts to appear at the Royal Hawaiian Supper Club was the Mills Brothers during the week they would entertain the ever-square Gerald Ford at the White House. Munley also inherited a dire financial situation and checks sent to entertainers bounced, which led to a $15,000 lawsuit by singer Jack Albertson. The club featured artists such as the Amazing Kreskin, Brenda Lee, and Sarah Vaughn.

Probably driven by economics more than anything, in October, 1977, the name of the club had become Louie’s Rock Concert City, but it was commonly known as Louie’s Rock City and they began to bring in rock music in the hopes of saving the business. In November 1977 Summersault and Cactus played, a few weeks later were Dr. Feelgood and Gentle Giant, Rick Derringer, Johnny Winter. Immediately, it became the place in NOVA for the burgeoning hard rock scene hosting brand new acts like Judas Priest before they hit the big time. Even though the club focused on rock music, it was cool to the new punk music coming out of New York. In 1977, the club cancelled the legendary punk bank the Nerves when they got a look at the band members.

By 1979, the owners of Louie’s Rock City accepted punk enough to host the Ramones. At first the Ramones were supposed to play on April 2, but it appears that show was cancelled for reasons lost to history. The Ramones would play Louie’s on July 27 and the show would be a cultural marker for the DC area. Of course, this wasn’t the Ramones first appearance in the DC area. They had played the Childe Harold October 22-24, 1976; October 11, 1977 at the Bayou; October 15, 1977 opening for Iggy Pop at the Baltimore Civic Center; and the Cellar Door with the Runaways March 19, 1978.

This time it was different because the punk scene in DC was coalescing around some kids for Northwest Washington, suburban Maryland and Northern Virginia. A young music promoter named Seth Hurwitz saw the Ramones were coming to Louie’s and decided to bring them down a day early for the premiere of the Ramones’ new movie “Rock and Roll High School” at the Ontario Theatre in Adams Morgan. On July 25, 1979, The Slickee Boys and Razz played to a packed crowd as the Ramones signed autographs and mingled. For many kids, this was the beginning of punk in Washington and Hurwitz would go on to own the 9:30 Club and founded the musical promotion company Live Nation. As “Rock and Roll High School” rolled fans danced in aisles to the music and cheered through best scenes. The newspaper described the crowd as a mix of punks, hippies, and lawyers ranging from “preteens to aging rockers”. The next day, the Ramones signed records at Penguin Feather at 5850 Leesburg Pike. The building has been torn down, but it was located roughly on the parking lot of the recently shuttered Borders Books in Crossroads Center.

|

| Ramones at Onatrio Theatre |

Sensing the excitement in the city, the Washington Post was on hand for the Ramones gig at Louie’s on July 27, 1979. Initially the Post dislike punk because it upset the neat order of Washington, which was neatly divided into the three strata of the city, black people, polite Washington, and hippies. Punk didn’t fit and the old curmudgeon of DC music Richard Harrington declared punk was the “music for empty spaces of the mind.” In his review of the earlier Ramones show at the Bayou, he sounded a hopeful tone that punk was a passing fad when he said that half the crowd was there “out of curiosity” and “a number left after it became apparent that a Ramones set consists of monochord songs.” It’s a bitch being a cultural arbiter when the great unwashed don’t heed your cultural orders.

In a rare moment of wisdom, the WaPo hired a decent reporter, named Joe Sasfy, to cover the new music scene. Sasfy managed to straddle his reporting between a sympathetic eye towards the new sounds, but always writing in a way that polite Washington could understand. Wisely, Harrington was allowed to go to bed at a decent hour on the night the Ramones played Louie’s and the Post sent Sasfy to capture a cultural moment for the DC area. Sasfy noted in his article the Ramones fans showed up and were surprised by Louie’s dress policy and had to sew the tears in their clothes to get in. As the soon-to-be singer for Minor Threat and later Fugazi, Ian MacKaye recalled:

I have great memories of seeing the Ramones in 1979 in Virginia, a bit further out in the suburbs at a place run by the marines. It had almost a Hawaiian theme, an old-school bar/lounge kind of place, with cocktail waitresses and stuff. There was a huge line of people waiting to get in the show, and there was a skirmish at the front of the line, and the word spread like wildfire and came down the line that there was a dress code, and you couldn't have torn jeans. But you were going to see the Ramones-everyone had torn jeans! It just rippled: Dress code, they won't let you in with torn jeans. Suddenly-it was in a little shopping mall-people made a beeline for the pharmacy and started buying needles and thread. There was a whole fucking parking lot of people sewing their jeans up trying to get in this gig.

It’s surprising that Louie’s had a dress policy given they hosted Judas Priest and other hard rock bands. This incident may have stemmed from the club owners nervousness about hosting a punk show and was implemented as a way to control the crowd. Despite this barrier, the crowd packed into Louie’s to see one of the great Ramones shows. One recent high school graduate named Henry Garfield was there. The show would transform his life and he would form a band called Black Flag and change his name to Henry Rollins. Rollins speaks often about his experience at the show saying he “never got over that gig”. Later he said,

I saw them at a small club, Louis’s Rock City, which is now a Chinese restaurant, in Falls Church, Virginia, right over the bridge from DC. It was one of those over-sold events where there’s no breathable air. I was right in front of Dee Dee. It was the first time I can remember being really star-struck. A lot of us were just coming out of arena rock. I’d seen Led Zeppelin a year and a half before. But with the Ramones there was no barricade, I could’ve leaned over and grabbed the head-stock of Dee Dee’s bass. Johnny and Joey were very tall people, so they had quite a presence up close. There was no space between the songs; they just beat you over the head with it. It’s a hot night, there’s no air, it was kind of painful, really loud, and we knew every word to every song – so you walked out of there, knowing you’d been put through something. You felt physically pummeled; it was really a full-on experience. I realized I was gonna be in this mindset for the rest of my life. I had no idea then what I was doing with my life. I had a minimum-wage job, $3.50 an hour, and a really bad apartment with a friend. So the Ramones had a very big impact on me.

These few days the Ramones spent in the DC area would change the landscape of the city and in short order it would become one of the centers of punk music in the United States. The Ramones at Louie’s would echo through the years as DC developed a unique and thriving punk and new music scene that would bring sounds and clubs the city now considers routine.

As for Louie’s Rock City, the club would go on to host memorable shows by Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry in 1981. By this mid-eighties, it became primarily known for heavy metal and hosted a regular Battle of the Bands featuring local heavy metal bands trying to break into stardom. The club closed in 1989 and became a Chinese restaurant. Today it is the Babylon Futbol Club featuring soccer, Arabic, Caribbean, and Latin music.

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

The Admiral Grill

Northern Virginia was a center for the development of country music and especially blue grass as I’ve mentioned before on this blog. One of the legendary moments in the expansion of blue grass beyond local hillbilly migrants came in 1957 at a local watering hole called the Admiral Grill. The Admiral Grill was located on Columbia Pike at the current site of the storage company and stood roughly where the main office/entrance currently stands. The restaurant was there from at least the mid-fifties until the mid-sixties before becoming a restaurant called Westwoods, then a furniture store and finally a storage company. Back in the late fifties and early sixties was just a simple crossroads with a few small restaurants and an airport at the current site of Skyline Towers.

In 1957, Northern Virginia was filled with musicians playing a new brand of “folk” music that was a new take on old-time mountain music. It was called a variety of things before the name blue grass stuck deriving from the name of Bill Monroe’s backing band, the Bluegrass Boys. The sound was very popular among the transplanted Virginians and Carolinians yearning for the sounds of home, but it was stuck being played in small bars and restaurants with limited appeal.

The event happened by accident on July 4, 1957 when the Buzz Busby’s Bayou Boys were heading back to DC after playing a gig on the Eastern Shore when their car crashed. The band’s banjo player, Bill Emerson, had been riding in a separate car and was determined to keep the gig that night at Admiral Grill. He called on a guitarist, Charlie Waller, mandolinist John Duffey, and bassist Larry Leahy to fill in.

The gig went so well that the group formed a band and settled on the Country Gentleman because the members were city boys rather than “mountain boys”. The band they would go on to form was different from many country or folk bands playing around DC because they were young and spent most of their lives in an urban setting.

The band would become the most important and influential bluegrass band and formed a second-generation of bluegrass musicians that would spearhead the growth and popularity, particularly in the DC area. The band took influences from many genres, moving the music beyond its strict mountain roots by exploring rock and jazz. This widened bluegrass’ audience beyond the ex-mountain people into young urban kids from blue collar bikers to college kids.

The music would find a home in the Birchmere on Four Mile Run Dr. in Arlington and the Shamrock on M Street in Georgetown where rowdy hillbillies and college kids would mingle to the changing sounds of bluegrass.

Sadly, besides this single evening of fame, almost nothing is known about the Admiral Grill. The building was unceremoniously torn down to make way for development of the storage company and Radley Acura. If you drive behind Radley, you can get a sense of what Bailey’s Crossroads was like before the current development. One building that stood at the same time as the Admiral Grill was the service garage for Radley Acura, which was a auto repair shop. Otherwise, the Admiral Grill lives on in legend only.

Sunday, August 14, 2011

The Ku Klux Klan and the Redneck Mafia in the twenties

|

| The Ballston Klan No. 6 gathered on their field |

Virginia passed liquor prohibition in 1916, one year before Washington DC, and four years before the federal law. The Klan aligned with the Anti-Saloon League and the Women’s Temperance Union to pass the law and worked to enforce it when they perceived local law enforcement as too lax. The division over prohibition created splits in the community between “wets” and “drys” that translated into the Democratic Party. In many parts of Virginia, this split caused an internal civil war among Democrats, but in Northern Virginia, the Klan seemed to ally more readily with the Republicans. Locally, the Democrats were more liberal and included more ethnic whites whereas the Republicans tended to be conservative Protestants, which more closely aligned with the Klansmen.

By 1922 the Klan had gained significant membership in Northern Virginia, which Goblins (the title for recruiters) brought in by a practiced script and salesmen practices. The strategy that helped the Klan thrive was to split the initiation fee among many stakeholders and the Goblins making a similar living to any well-paid salesmen. One Goblin in DC sued the Klan for $15,000 owed to him for his recruiting activities, which gives us a sense of the amount of money the Goblins earned. However, the problem with broad incentivized recruiting is an organization may get large numbers, but it will inevitably recruit undesirable members. By the early twenties, the Klan had become a large organization made up of a broad array of people that included men involved for fraternal reasons as well as thugs joining for less noble reasons.

In many cases, Klan members tried to use their connections as a cover for crimes or would overtly invoke the KKK name to intimidate blacks, Jews, or Catholics. For example, on September 1922, a man named Frank Fields went to the home of a young black girl and claimed he was a member of the KKK before he attacked her. The article was not clear on the nature of the attack, but implied it was a sexual assault. What preceeded the attack is also unclear; it may have been simply drunkenness, thuggery, intimidation, or revenge. Frank Fields was involved in bootlegging and had been arrested for shooting at another man on North Pitt St. near King St. in Alexandria. As was customary for the Klan when a member was put in the spotlight, the KKK wrote a letter to Frank Ball, the Commonwealth Attorney, denying Fields membership in the Klan. However, it is hard to believe Frank Fields wasn’t a member because his brother, Howard, was running for Sheriff at the time against AC Clements with the vociferous backing for the KKK. Howard Fields and Clements would have a decade long rivalry rooted in prohibition in which Klan and other drys perceived Clements as being weak on gambling and prohibition, but Fields, at least superficially, supported prohibition.

They also accused Frank Ball of being intentionally laggard on prosecuting gambling, but Ball struck back saying the Klansmen were cowards because they make unsubstantiated charges. Ball was a liberal on segregation and would go to have a distinguished political career and ultimately represent Arlington in the desegregation of the schools. Ball summoned the Klan to appear in front of a grand jury to show proof of their charge, but when the Klan members gave testimony; the grand jury could find no proof that county officials were culpable. However, the Klan regularly sent members and associates out to case gin joints or gambling rackets and in one case this amateur detective work paid off because police busted a gambling ring at the Hilltop Country Club in Arlington. Police raided the country club and found gamblers including the lookout George Mater from Bladensburg – a known thug and bootlegger.

Meanwhile in Alexandria in late 1922, the Klan had enough with bootleggers and gamblers, so they hung placards across the city so residents would wake on Monday morning to a warning, "We are here because certain conditions demand out presence. We know within the city of Alexandria the bootlegging traffic is increasing to alarming proportions. The authorities are apparently unable to cope with this deplorable situation." The signs alerted residents that the Klan would be collecting evidence on bootleggers and gamblers to turn over to police. The newspaper noted that many Alexandrians snickered at the signs not believing the KKK had the strength or reach to put a dent in the thriving illicit industries. However, the Klan paid for a Private Investigator to mingle with bootleggers and pinpoint the speakeasies. In 1923, the Private Investigator held a party with a bunch of his new bootlegger friends, but it was sting for police to arrive and arrest them. That same month, police raided two speakeasies, the Majestic Lunchroom on King St, arresting Peyton Ballenger, and the Black Cat on South Union, arresting Leroy Beach based on evidence gathered by Klansmen.

Despite this crusade on behalf of the drys, the local KKK officials grew increasingly worried about the public perception of them as a violent organization. In March 1923, they felt the need to tell county authorities that they would help prosecute “people who make threats in the name of the KKK” and reminding them that “any communication of our order, is written on official stationary and signed by some officer of the organization.” Clearly the organization was doing well in publicity, but at the street level many perceived the organization as a group of thugs. While street level violence undoubtedly occurred under the banner of the KKK, the Northern Virginia chapters engaged in intimidation too subtle for newspapers to pick up. For example, the Ballston Klan would organize parades through the county in cars laden with food and clothing for the needy. Conveniently, many of these needy folks were Catholic, blacks, and Jews that the organization railed against in their rallies. Imagine the terror of being a black family visited by a parade of Klansmen dropping off food and clothing. While the act gained positive press, it was clearly intended to frighten foes without the messiness of violence.

|

| Klan distributing baskets |

The strength of the KKK grew into Election Day 1923 when they successfully elected Howard Fields for Sheriff. Fields had served before, but AC Clements had defeated him in the prior election. Fields alleged that Clements had beaten him organizing bootleggers and gamblers, which Clements denied. It is pretty clear that Fields was a member of the Klan because the chair of his election committee was Howard Bitting who would go on to be the leader of the Ballston Klan in the thirties. Clements was allied with Frank Ball and was Catholic, which was the ultimate disqualifier for public office in the eyes of the Klan. Fields was a true believer and allegedly promised to bring a second heaven to Arlington, but he regularly pulled strings for fellow Klansmen such as EE Naylor, whom he helped get out of a ticket for an expired auto tag. The Klan was so excited to have one of theirs leading law enforcement in the county that they had an impromptu parade across the county including 75 cars with the two leads boasting 8-feet tall crosses lit up.

Strangely, a few days later a group of men dressed in KKK regalia passed a saw to two inmates in the Arlington jail so they could cut the bars and escape. One escapee was Earl Blundon who was a lifelong criminal involved in burglary, bootlegging, and other crimes. Arlington police searched for him, getting so many tips from fellow bootleggers that police wondered if he had made enemies with other Arlington criminals. Perhaps Blundon had become allied with another group of bootleggers and the other criminals wanted him out of the picture.